In the artist Faith Ringgold’s children’s book “Harlem Renaissance Party,” Lonnie, a young boy, and his Uncle Bates spend a whirlwind day in nineteen-twenties Harlem meeting Black artistic greats, including Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, and Coleman Hawkins. At the end of the tour, Lonnie says to his uncle, “Black people didn’t come to America to be free. We fought for our freedom by creating art, music, literature, and dance.” His uncle responds, “Now everywhere you look you find a piece of our freedom.” This understanding of the inescapable entanglement of joy and sorrow—and of hardship and creation—is one that echoes through much of Ringgold’s work, which can be seen, in a major retrospective, “Faith Ringgold: American People,” at the New Museum, in New York City, through June.

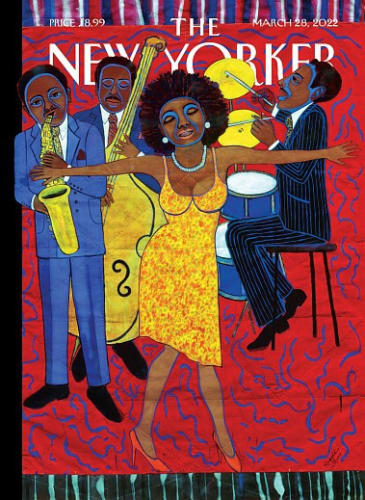

This week’s cover, for the Spring Style & Design Issue, features a piece from Ringgold’s “Jazz Stories” series, which she began in 2004. In it, Ringgold, who was born in Harlem in 1930, celebrates the music that has provided her with a lifetime of inspiration.

Can you talk about your connection to jazz and music?

I have spent a lifetime listening to the great music of Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, and others. Many of these musicians also lived in Harlem, so, even though they were stars, they were also neighbors. I grew up with Sonny Rollins. My first husband, Earl Wallace, was a classical pianist and composer. Our home was lively with musicians, such as Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, and Jackie McLean, among others.

These silkscreens were part of my first jazz series, which I dedicated to Romare Bearden, the greatest of the jazz painters. I could easily spend the rest of my life singing my song in pictures.

You have also been an educator for a long time. Did teaching change your work?

I grew up with role models in my family who were teachers. The most notable was my mother’s father, Professor B. B. Posey. Over the course of more than forty years, I have taught students from junior high to college. In 1985, I was offered a position as a full professor in the visual-arts department at the University of California at San Diego, teaching studio courses in drawing and painting. Teaching art brought a richness to my life and my art that could never have occurred otherwise. I couldn’t be more pleased to describe myself as both an artist and a teacher.

You’ve painted, quilted, sculpted, and authored children’s books. Is there a medium where you feel most at home?

Since the nineteen-fifties, I have worked in sixteen distinct mediums, including oil paintings, story quilts, tankas, soft sculptures, prints, masks, book illustrations, and more. I’ve never limited myself to one medium or technique. I’ve used each to tell my story, to express what I needed to express.

You’ve been creating art for decades. What’s one thing that you wish you’d known when you were starting out as a young artist?

I think about the things people did tell me, instead of what I wish I’d known. My mother told me I would have to work twice as hard to get half as far. My father always said, “We ripped up the pattern for this one.” And I tell every young artist that anyone can fly—all you have to do is try.